Introduction

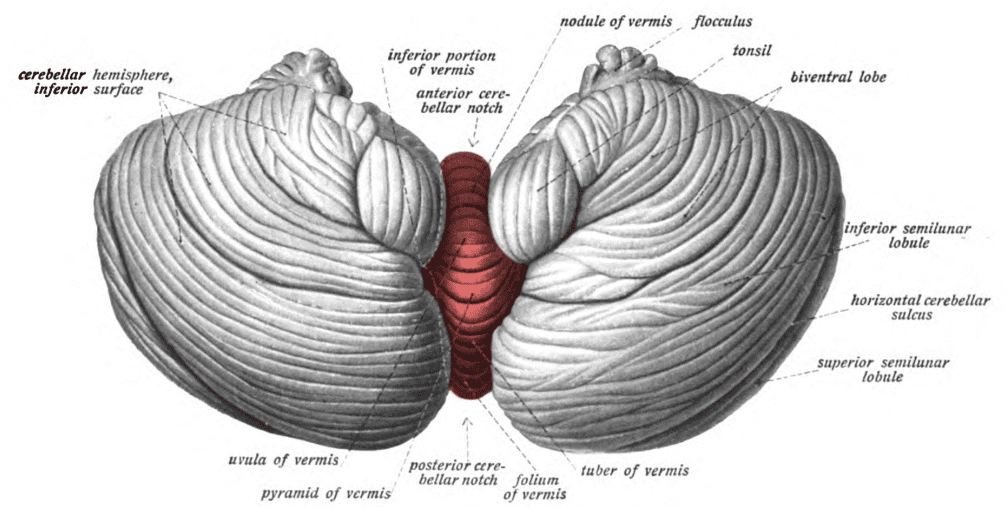

Medulloblastoma is the most common type of malignant (cancerous) primary brain tumour in children. It typically arises from the cerebellum within the vermis (“worm”), located at the lower back region of the brain. This area of the brain is involved in balance, muscle coordination and movement.

(File:Sobo 1909 654 Cerebellar vermis.png – Wikimedia Commons, 2020)

Grading of central nervous system (CNS) tumours is based on cytology, mitotic activity, microvascular proliferation, and necrosis: all medulloblastomas are aggressive tumours, and are therefore classified as grade IV [1]. These tumours may spread to other parts of the brain and/or the spinal cord via cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Normally, CSF functions to protect, provide nutrients and remove waste from the CNS, however, may carry cancer cells as it circulates in and around the brain [2].

Clinical presentation

Medulloblastomas often present with non-specific symptoms between the ages of 0-10 years old. It is often difficult to differentiate from other types of CNS tumours based off symptoms alone. 70-90% of medulloblastomas develop in the 4th ventricle, close to the the cerebellum, therefore signs of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) are usually initial indicators: the classic triad includes morning headaches, vomiting, and lethargy (extreme sleepiness). As tumour size increases, cerebellar dysfunction becomes apparent. Problems with walking, balance and/or fine movements and their coordination progress with time, particularly affecting the lower extremities [1]. It is common for children to have symptoms for weeks to months before a diagnosis is confirmed [3].

Additional manifestations of increased ICP include:

- Blurred and/or diplopia (double vision)

- Confusion

- Seizures

- Syncope (passing out)

If the tumour metastasizes (spreads) to another part of the body, for example, the spine, this may lead to limb weakness or numbness, back pain and/or changes in bowel or bladder function [1].

Risk factors

Medulloblastoma is a rare condition that can occur at any age, although are most common in young children [2, 3]. The incidence is slightly higher in males, however, subgroups with unfavourable genetic associations are more likely to have a poor prognosis [2, 4]. Typically, children are diagnosed between 3-4 or 8-10 years of age [3]. In adults, medulloblastomas are most common between the ages of 20 and 40. [1]

Unfortunately, the underlying cause is unknown. Studies have investigated parental, environmental, and maternal factors as potential links to medulloblastoma formation to no avail. However, one study demonstrated that mutations within germ cells (cells that develop into sex cells – sperm/ovum) may predispose an individual to familial or heritable medulloblastoma. This type of mutation can be associated with a condition called Turcot syndrome, which also significantly increases the risk of colorectal cancer [3].

Types of medulloblastoma [4]

Recent research on the molecular abnormalities of medulloblastomas has helped to identify four main subgroups in children. Despite this progress, our understanding of adult medulloblastoma remains an area for further investigation.

- WNT medulloblastoma – the most well-understood subgroup, accounts for 10-15% of cases. The average age of diagnosis is 10 years old and occurs more frequently in females. Mutations in WNT oncogenic (cancer promoting) genes activate an abnormal signalling pathway named the Wingless signalling pathway.

- SHH medulloblastoma – this subtype is more common than the WNT subtype, frequently affecting patients under 3 or over 16 years of age. It may present with an associated condition known as Gorlin syndrome, a rare type of skin cancer that affects multiple parts of the body. Only about 5 in 100 patients with Gorlin syndrome will also develop a medulloblastoma. SHH stands for Sonic hedgehog signalling pathway, involved in regulating key developmental events and tumour formation. Abnormal activation of this pathway through genetic mutations lead to medulloblastoma in 30% of affected children [3].

- Group 3 medulloblastoma is most common in males between the ages of 1-10. With this subtype, it is common that the tumour presents with metastasis, meaning that it has already spread to other parts of the brain and spinal cord by the time of diagnosis.

- Group 4 medulloblastoma – this is the most common subgroup, accounting for between 35-40% of all cases. They are most common in mid-childhood but can occur at all ages. No clearly defined signalling pathways have been identified, however, certain gene mutations are indicated.

Diagnosis

If a patient is suspected to have a brain tumour, prompt referral to a specialist at hospital is necessary for diagnosis. To begin with, the doctor will ask questions and gather information about symptoms and previous medical history. This is followed by a neurological examination – the doctor tests for normal vision, hearing, balance, coordination and reflex responses. Any abnormal signs help to indicate which part(s) of the brain may be affected. Keeping mind that brain tumours are a broad category, further tests are needed to narrow down the type, effects and spread of the tumour.

Following the examination, imaging investigations like computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are used to visualise the brain. These machines compile several cross-sectional 2D images of the brain that can be analysed to gain a better understanding of the location and size of the tumour. Medulloblastomas usually appear as a solid mass in the 4th ventricle or cerebellum. Often, contrast dye is injected into the blood vessels to highlight internal structures from their surroundings. This is a common method used to locate tumours in the brain. Importantly, imaging can also show if there is a buildup of fluid causing increased pressure in the head. This is common in medulloblastomas due to their location. If the 4th ventricle is blocked by a tumour mass, fluid that normally circulates without obstruction begins to accumulate and leads to a condition called hydrocephalus. Sometimes this can visibly enlarge the head and may lead to brain damage. If imaging does not reveal the diagnosis, a biopsy may be carried out. This procedure involves taking a sample of the tumour tissue which can be analysed microscopically to identify features that indicate the type of tumour.

Treatment

The treatment of choice is surgery to remove the tumour, followed by either radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. The precise treatment plan depends on many factors such as: age, general health, tumour subtype and its location, size and potential spread [2].

Surgery to remove, or excise a tumour aims to take out as much of the tumour as possible, whilst making sure that any surrounding healthy tissue remains intact. It is often not possible to remove the entire tumour: medulloblastomas typically form near crucial structures in the brain where significant damage should be avoided. For this reason, patients receive additional treatments following surgery to kill any remaining tumour cells. The excised tumour tissue is sent to a laboratory for inspection. This information is used to tailor a specific treatment plan [3]. Usually, removal of the tumour is enough to relieve the buildup of fluid. If not, further steps are required.

As mentioned before, the technical name for fluid buildup in the brain and around the spinal cord is hydrocephalus. This increase in volume leads to a raised intracranial pressure and may require surgery for relief. Neurosurgeons can insert a cerebral shunt to create a pathway between open spaces in the brain (ventricles) and the peritoneum (a cavity within the abdomen). This reintroduces a pathway for CSF to flow and restores normal intracranial pressure around the brain. [2]

Treatment following surgery often involves radiation therapy, where high-energy beams (X-rays or protons) are used to target and kill remaining cancer cells. Nowadays, this is only recommended in children older than the age of 3 to prevent damage to the developing brain. In some cases, chemotherapy may be used. This method utilises liquid chemical agents that can be infused into the bloodstream via a vein. Chemotherapy is sometimes also used to shrink the tumour prior to surgery. This can reduce the risk of brain damage during surgery and improve clinical outcomes post-operatively.

Complications associated with medulloblastoma

Complications can be separated based on their cause. Those directly related to the disease include metastatic spread, usually to the brain or spinal cord. In rare cases, the tumour may spread outside the CNS to the bones and lymphatic system [1] – a network that transports lymph fluid around the body which functions to remove toxins and waste material. Due to the difficulty in complete removal of medulloblastomas, recurrence of disease is possible [3].

Other complications are associated with the method of treatment. Surgery carries its own risks such as bleeding, infection or shunt malfunction. These risks are considered against the benefits of surgery and patients are fully involved in the decision-making process. Side effects induced by radiotherapy and chemotherapy are usually temporary whilst the treatment is ongoing. Nonetheless, these methods may have serious long-term health consequences depending on the patient and their clinical context. Children may face difficulties at school and can struggle to meet normal developmental milestones, thus careful monitoring is necessary for support [3]. Most patients do not have any activity restrictions outside of limitations imposed by the disease itself. However, those with a central line (a type of intravenous access portal) and/or cerebral shunt should avoid high-impact sports for safety.

Prognosis and follow-up

Understanding the impact of living with a brain tumour on an individual depends on multiple factors. Five key aspects to consider when assessing prognosis are: age at diagnosis, spread at the time of presentation, extent of surgical removal, molecular subtype, and microscopic features of the tumour. While evidence can provide an estimate prognosis for various patient subgroups, doctors do not rely on this data alone to predict patient outcomes [4]. Treating and monitoring patients is an ongoing process, and doctors aim to integrate evidence, expertise, and individual patient circumstances in their decisions to provide the best care possible [5]. As research, technology, and our understanding of this disease continues to expand, the statistics and future prospects are likely to change [6].

Patient education is a key aspect of monitoring. Doctors should instruct patients on proper hygiene techniques to minimise the risk of infection and provide advice on when to seek medical attention.

Follow-up care involves monitoring for recurrence and in some cases, managing long-term side effects of medulloblastoma. Regular health check-ups include blood tests and/or imaging scans. It is also important to consider the mental health and well-being of the child and family members. Late side effects can lead to problems with the heart, lungs and secondary cancers. These problems often overlap with emotional challenges such as anxiety, depression and problems with cognitive function. A child’s quality of life is extremely important in managing aftercare. The term “survivorship” encompasses the everyday hurdles that a patient must endure to cope with a medulloblastoma diagnosis. Integrated care includes support from not only the healthcare team, but also counseling services and assistance from a learning resource centre. Healthy living also means working towards a lifestyle that enhances the quality of a child’s future. As with any individual, health guidelines such as avoiding smoking, maintaining a healthy weight through diet and exercise, and managing stress are major factors in general health and wellbeing. Some patients may be recommended for rehabilitation which provides a wide range of services. Tailored programmes aim to increase patient independence and confidence in themselves [8].

Key takeaway messages

- Medulloblastoma is the most common high grade brain tumour in children.

- Medulloblastoma typically present with non-specific symptoms (morning headaches, vomiting and tiredness) or problems associated with cerebellar dysfunction (abnormal balance, walking, muscle coordination and movement).

- Medulloblastomas may be associated with specific genetic mutations, although the cause is generally unknown.

- Diagnosis involves a thorough history and physical examination, followed by imaging (CT, MRI) and biopsy for microscopic analysis.

- Surgery is the treatment of choice, followed by radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy to target any remaining tumour cells.

- Complications are associated with the disease, surgery or treatment. Regular monitoring is necessary to maximise patient quality of life and manage the risk of recurrence.

- Prognosis depends on many factors and will vary for every individual. Patients should be assessed and treated for both physical and mental health to optimise clinical outcomes.

References

- Institute, N. C. and Health, at the N. I. of (2019) Medulloblastoma. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/rare-brain-spine-tumor/tumors/medulloblastoma (Accessed: 5 April 2020).

- Mayo Clinic (2019) Medulloblastoma. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/medulloblastoma/cdc-20363524 (Accessed: 5 April 2020).

- Cancer Research UK (2019) Medulloblastoma. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/childrens-cancer/brain-tumours/types/medulloblastoma (Accessed: 5 April 2020).

- Commons.wikimedia.org. 2020. File:Sobo 1909 654 Cerebellar Vermis.Png – Wikimedia Commons. [online] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sobo_1909_654_Cerebellar_vermis.png (Accessed 6 September 2020).

- The Brain Tumor Charity (2016) *What is a medulloblastoma?*Available at: https://www.thebraintumourcharity.org/brain-tumour-diagnosis-treatment/types-brain-tumour-children/medulloblastoma/ (Accessed: 5 April 2020).

- The Brain Tumor Charity (2016) Medulloblastoma prognosis. Available at: https://www.thebraintumourcharity.org/brain-tumour-diagnosis-treatment/types-brain-tumour-children/medulloblastoma/medulloblastoma-prognosis/ (Accessed: 5 April 2020).

- Kool, M. et al.(2012) ‘Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: an international meta-analysis of transcriptome, genetic aberrations, and clinical data of WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4 medulloblastomas’, Acta Neuropathologica, 123(4), pp. 473–484. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0958-8.

- Cancer.Net. 2020. Medulloblastoma – Childhood – Follow-Up Care. [online] Available at: [https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/medulloblastoma-childhood/follow-care#:~:text=Care for children diagnosed with,is called follow-up care.](https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/medulloblastoma-childhood/follow-care#:~:text=Care for children diagnosed with,is called follow-up care.) [Accessed 7 September 2020].

Leave a Reply