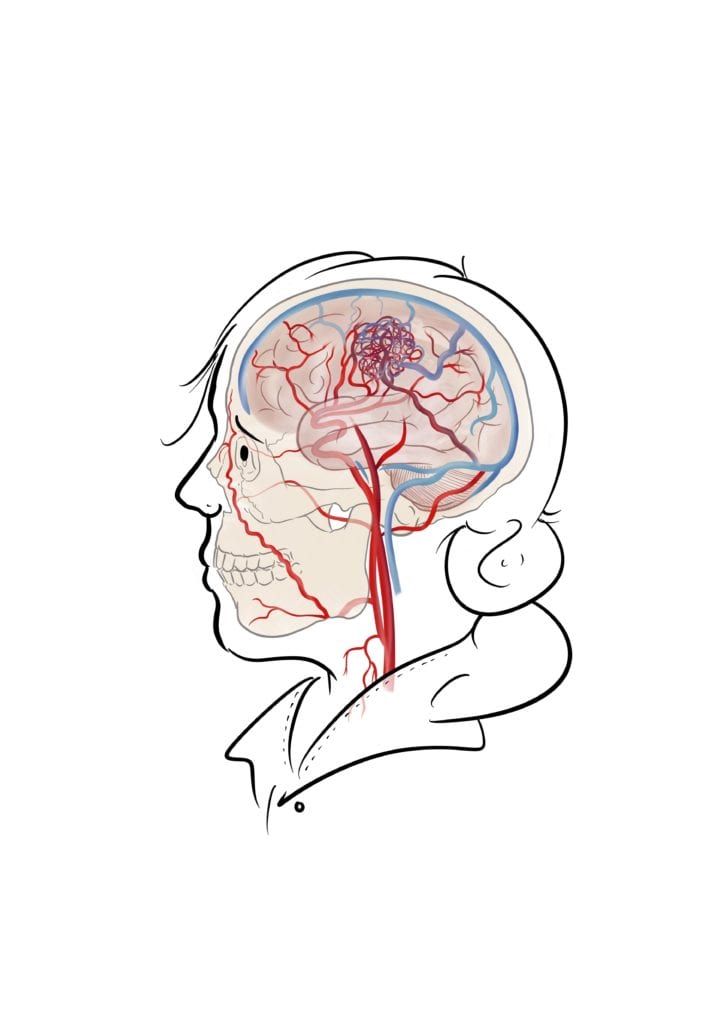

An arteriovenous malformation (or AVM, which is much easier to say) is an abnormal tangle of blood vessels that can occur anywhere in the body. Imaging tangled up headphones or Christmas lights, except instead of wiring, you have blood vessels. The most common location for these are in the brain, and this is what this blog post will focus on.

Why is an AVM bad?

Normally high pressure blood flows from the heart through thick walled arteries, then gradually loses pressure through capillaries and flows back to the heart at a low pressure in thin walled veins. In an AVM the capillaries are bypassed which means high pressure blood is flowing through thin walled veins, which aren’t designed to transport high pressure blood. This can cause the veins to bulge, enlarge or even burst! Because oxygenated blood in the arteries is also led directly to veins, this also means that the oxygen isn’t being delivered to some areas of the brain.

Key Clinical Features

Symptoms you might experience will depend on whether or not the AVM has ruptured, and it also depends on where in the brain it is. If an AVM is unruptured, you might experience:

- Seizures

- Changes in vision, e.g. double vision / loss of vision / drooping eyelid

- Headaches

- Dizziness

- A “whooshing” sound in your ears or head – known as “pulsatile tinnitus”

- Weakness, numbness or strange sensations in your arms or legs

About 50% of patients will present with an AVM rupture. This causes a bleed in the brain – you may experience the following symptoms:

- Sudden severe headache – typically described as a ‘thunderclap headache’

- Nausea and vomiting – you may feel the need to be sick or will vomit

- Stiff neck – a cramping, stiff feeling

- Blurred or double vision – any sudden change in vision is a sign to seek medical help

- Photosensitivity – person becomes irritated by light

- Confusion

- Slurred speech

- Muscle weakness

Major Risk Factors (Who is affected?)

AVMs are thought to be congenital, meaning they are present at birth. There are some hereditary syndromes that lead to an increased risk of having an AVM, such as Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) or Wyburn-Mason Syndrome. There have also been some reports of new AVMs forming several years after a head injury2. It is difficult to truly say how many people have an AVM, as many people may be living with one without symptoms and they are identified through investigations for something else (known as an “incidental diagnosis”). However a study by NHS England in 2013 found that the prevalence of new diagnosis may be between 1 and 10 per 100,000 people per year.

Risk factors for rupture include smoking, high blood pressure and contact sports.

Diagnosis

Ruptured AVMs will produce a bleed on the brain, which can be seen best with a CT Head scan. During a CT scan a special view can also be done of the blood vessels, known as “CT Angiography”. However the most accurate method of diagnosing an AVM will be through cerebral angiography, which is an investigation that involves putting a small catheter through a blood vessel in your groin up towards your brain. Dye will then be injected and lots of X-rays taken, which allows doctors to accurately see all the blood vessels.

AVMs can also be identified using MRI scans, and usually these will be done as a follow up for patients that are under investigation, awaiting treatment or being followed up after treatment.

Classification

You might hear your surgeon talking about a “Spetzler-Martin” score – this is a way of grading an AVM to help your team decide the best way of treating your AVM. The score is graded based on size, location, and venous drainage and ranges from 1 to 5.

Treatment

Immediate treatment will be done if the AVM has ruptured, which can sometimes be life threatening. After assessment with a CT Scan doctors may decide to put a small drain in to relieve pressure in the brain (Check out our post on EVDs here!), or take the blood clot out. However this is mostly to treat the effects of the ruptured AVM and not to treat the AVM itself.

Surgical

Surgical treatment for AVMs very much depends on where it is and how big it is. During surgery for this the skull is opened up and once the AVM is found, your surgeon will very carefully try to seal all of the abnormal blood vessels to prevent bleeding, then take out the “nidus” (the main body of the AVM). A special injection of a dye called ICG can be used to assess the blood flow during the operation and this can tell the surgeons whether or not the AVM has been successfully removed, or if there are any remnants. An angiogram, which is the gold standard imaging, is usually performed after surgery to definitively check if the AVM has been removed.

Endovascular

Some AVMs can also be partially or completely obliterated by an “endovascular” procedure under general anaesthetic. This is where – just like in an angiogram – a small catheter will be guided into the brain to where the AVM is through the artery in the groin. Once the tube is near the AVM and it has been identified, a kind of “superglue” called Onyx will be injected into the AVM and sometimes its “feeding” vessels. This will restrict the blood flow to the AVM and it will eventually shrivel up around the glue. The glue will stay in your brain lifelong and can still be seen on subsequent scans. This is called glue embolisation.

Radiation

In some cases, it is too dangerous to treat an AVM with surgery or embolisation. There is one more method of treatment though: “Gamma Knife” – a type of radiosurgery. Similar to radiotherapy for cancers, this uses strong beams of gamma radiation that are targeted on the AVM and its feeding vessels, which will cause it to close up and die over time. This procedure needs a lot of planning and a lot of scans.

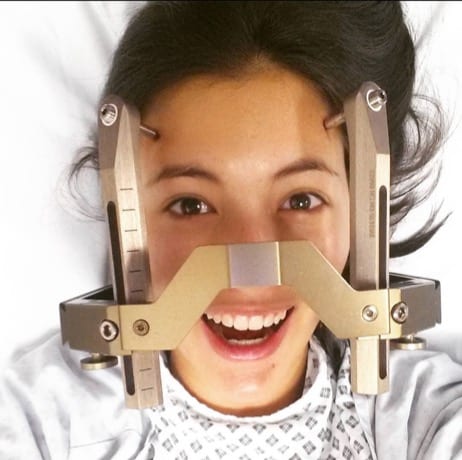

On the day of the procedure you’ll have a special frame fitted to your head (see picture) which can then be bolted into the table – this is to keep your head perfectly still, which is very important to make sure the radiation hits the AVM and not something else! When the frame is fitted you’ll have an MRI scan and an angiogram so that your surgeons can plan the radiation, then you’ll be put in the Gamma Knife machine to begin the procedure. This is done whilst you’re awake, and can last a few hours depending on how complex your AVM is.

The Gamma Knife machine is very similar to a CT or MRI scan – where your head is inside a giant donut. As your head will be bolted to the table you’ll be unable to move it, but your surgeons and nurses can get some pillows to support your neck and play the radio so you don’t get too bored! Gamma Knife radiation can take up to 5 years to see any effect so you’ll be followed up regularly with scans and appointments.

Combined

Treatment of an AVM can be very difficult depending on how big it is, where it is or if it’s bled. Sometimes your surgeons may decide to treat it with a combination of different methods. The key thing is to ask your surgeons lots of questions so you can decide together the way forwards.

Medical

There is no known drug to treat the actual AVM, but you may be started on anti-seizure medications or medications to bring down any swelling in the brain. You might also be started on medications to help bring your blood pressure down or given some advice on smoking cessation.

Conservative

In some cases, it may simply be too risky to treat the AVM depending on where it is in the brain. In this case your team will conduct check ups on you regularly with scans and clinics. You may be started on medications that are mentioned above or be asked to make some lifestyle modifications to prevent the risk of rupture.

Complications

Unfortunately, the most serious complication is how half of AVMs present – when they bleed. This can lead to visual loss, memory loss, limb weakness or in the most serious cases, coma or death. Thankfully the latter only happens in a small amount of cases – with timely intervention many who suffer a rupture can make a good recovery.

Complications of unruptured aneurysms can involve seizures, headaches and visual changes. The main aim of managing an AVM is to avoid it from rupturing in the future.

Long Term Picture

Many people with a ruptured AVM can make an excellent recovery. However in the case of a bleed due to AVM rupture:

- Treatment and improvement can continue for up to 18 months

- 1 in 4 will completely recover

- 1 in 4 had changed working hours or reduced work duties

- 1 in 4 had stopped work

- Some patients describe changes in their mood or emotions

You’ll be followed up for a few years after treatment of your AVM until your surgeons are happy that the AVM has been completely obliterated. Currently screening of family members for AVMs is not recommended by the NHS unless if a genetic condition, such as HHT, is known about. You might however be recommended to undergo genetic testing for HHT if there is a family history of multiple AVMs or small haemorrhages in other parts of the body.

What can I do to prevent myself developing an AVM?

Sadly as AVMs are thought to be present at birth, there is no way of knowing how to prevent developing one. However you can minimise the risk of it rupturing through a healthy lifestyle such as stopping smoking, exercising regularly, ensuring blood pressure is not too high and avoiding illicit drugs such as cocaine.

Key takeaway messages

- AVMs are tangles of abnormal blood vessels that are thought to be present from birth

- They can cause symptoms by “stealing” blood from important areas of the brain, or rupturing

- The most serious complications happen when the AVM ruptures, which can lead to permanent disability or death

- Diagnosis requires angiography with a CT or MRI scan

- There are 3 different methods of treatment (surgery, embolisation or radiation) which can be done individually or in combination

- You can reduce your risk of rupture by adopting a healthy lifestyle such as exercising regularly, stopping smoking and keeping your blood pressure within normal limits

References:

- https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2013/10/d05-p-c.pdf

- https://thejns.org/pediatrics/view/journals/j-neurosurg-pediatr/14/4/article-p418.xml

Gwen Evans

Brainbook Treasurer

Gwen is the current Neurosurgery Education Fellow at The Royal London Hospital and is an avid baker.

Merlin Strangeway

Medical illustrator

Merlin is an award-winning medical illustrator and creator of drawntomedicine.com

Very sadly lost my sister in July , she was 60 yrs old , we had been aware of her Ilness for 30 years when she had a bleed, we were told it was an Anuersm until 5 yrs ago when we were told it was actually an AVM, after a massive bleed in July she sadly lost her life, it is good to see awareness being made, I had never heard of an AVM until we were told that my sister had one