Introduction

An arteriovenous fistula (AVF) is an abnormal connection between an artery and a vein that can occur in the layers around the brain and spinal cord, as well as other areas of the body where such vessels are in close proximity. They also tend to be acquired following some sort of injury, as opposed to inherited. This is the exact opposite of the related pathology, (link) the arteriovenous malformation.

Physiology

Normally, arterial blood flows under high pressure, while venous blood normally flows under low pressure. When flow from an artery goes directly into a vein, high pressure blood flows into a slower, low pressure system. This can congest the brain’s venous system and lead to certain symptoms.

Risk Factors

Most frequently, AVFs affect people who are 50-60 years old but can occur in younger age groups as well, including children.

The reason for fistulas occurring is usually unclear, but research points to them developing over time rather than being inherited. Their presence may result from traumatic head injury, fractures, infection, previous surgery or tumours, essentially anything that you’re not born with that could compromise the linings of the brain and spinal cord.

Where inheritance does play a role is a condition called Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia (or Osler-Weber-Rendu Syndrome). In this case arteriovenous connections are encouraged to form across the whole body on a genetic level

Categorisation

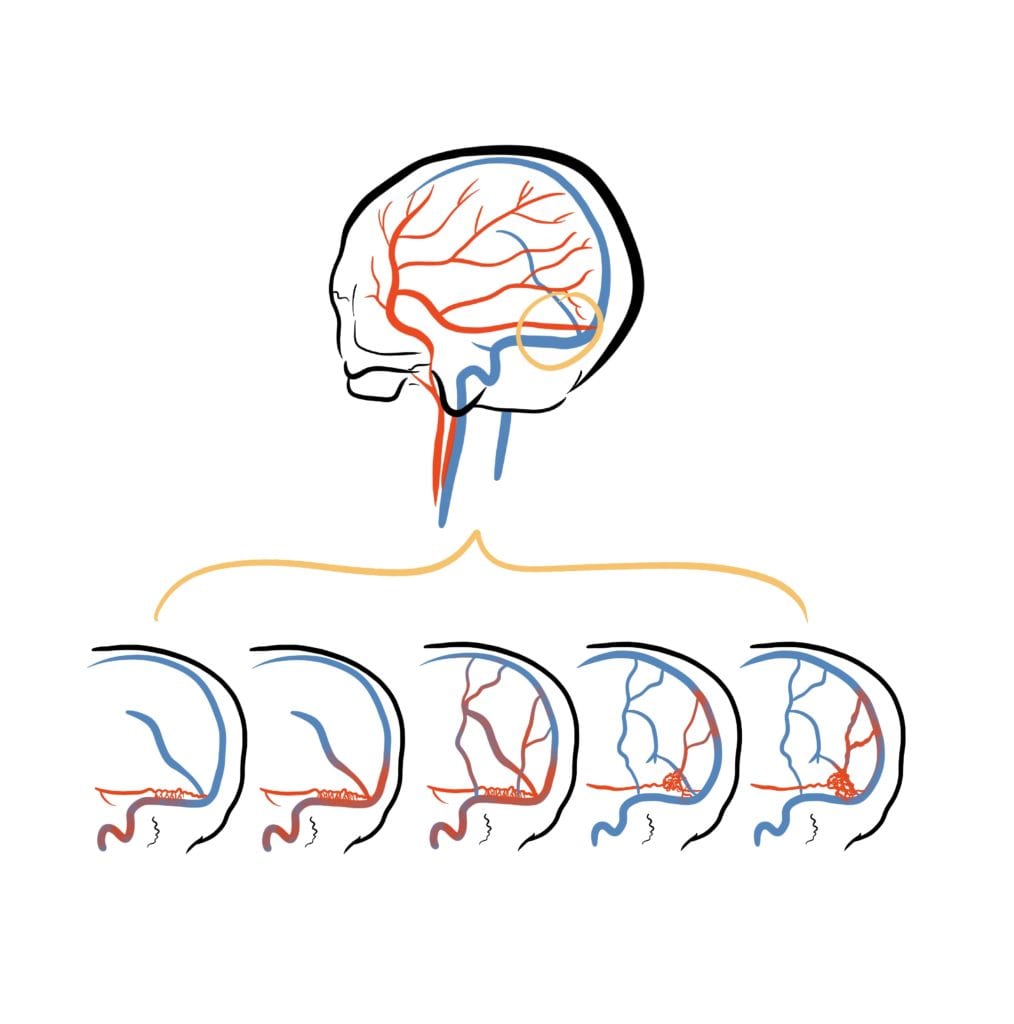

There are two types of AVF:

Dural – within the coverings of the brain and spinal cord; often form as a result of the large venous sinuses (link) being narrow or blocked. They account for 10-15% of all intracranial vascular malformations and are the most common vascular malformation of the spine.

Carotid-Cavernous – at the back of your eye in a small space called the cavernous sinus, through which the carotid artery passes.

These pathologies occupy different areas within the skull, but there essentially quite a lot of symptom overlap between the two.

Symptoms and Signs

Symptoms can be divided into aggressive or benign. They are often dependent on the size and location of the fistula itself.

Whilst some people don’t have any symptoms at all, those with relatively benign symptoms typically experience one of the following:

- Hearing issues, such as hearing a rhythmic humming noise that follows the same rate as your heart (a bruit, also known as pulsatile tinnitus)

- Visual problems such as blurry vision, your eye bulging out or moving to one side, swelling of the eye lining, redder and more obvious vessels on your eye itself and difficulty moving your eye within its socket. These tend to be progressive.

In more extreme cases, perhaps due to extensive progression over days to months, seizures, speech or coordination issues, or memory problems can develop.

However, if there is an acute catastrophic event, such as bleeding in the brain (haemorrhage), sudden-onset headache with neurological deficits corresponding to the affected area will occur (e.g. weakness of a limb).

These, certainly, require emergency intervention.

Diagnosis

The most appropriate initial will be diagnosed with CT scans and MRIs initially.

Angiography – where imaging is done of the vessels after an injection of contrast – can then be used to define more specific details such as its location, anatomy and structure.

Treatment

There are different options for treatment, but there are 3 main methods:

Embolisation: a long, thin tube (catheter) is inserted into a blood vessel in the leg or groin and threaded to the blood vessel leading to the AVF using X-ray imaging. A coil or a glue-like substance is then released to block the fistula.

Stereotactic radiosurgery: precisely focused radiation is targeted at the fistula to block it off.

Surgery: a craniotomy is performed to remove the fistula directly or, in cases of haemorrhage, to relieve brain pressure and prevent rises in intracranial pressure (Link to craniotomy blog and ICP articles).

Follow up

It’s not common at all, but there are case reports of AVF recurrence following their removal. These occurred within months to years, but often not enough to cause symptoms. It may be the case that this is more likely if there is a prolonged blockage of your venous sinuses for example, but this is still an area undergoing research to understand the exact mechanism.

Either way, comprehensive follow up is needed following your procedure to see how you and your brain/spine are coping post-procedure. Depending on the team in charge, and your own medical background, follow up duration may range from 1 month to several years if need be.

Key Takeaways

- There are two categories of Arteriovenous Fistula

- They are typically acquired through some sort of pathological event, rather than inherited

- They present progressively with comparable symptoms, or acutely with haemorrhage or neurological deficit

- Most are benign

- Elective or emergency procedures are required to correct severe cases

Jessie So

Brainbook Ambassador

This article was written by Jessie So

Merlin Strangeway

Medical Illustrator

Merlin is an award-winning Medical Illustrator, Writer, Educator and Director of ‘Drawn to Medicine’. She strives to visualise information in a way that makes it inclusive, engaging and just for both clinicians, patients and the general public.

Excellent article! I would like to thank you for the efforts you have made in writing this article.