A ventriculo-peritoneal shunt is the most common long-term treatment of hydrocephalus. VP shunts have been in use for the past seventy years and are constantly evolving to meet the patient needs better. Nowadays there are different types of shunts that can be inserted, and the decision on which shunt should be used depends on the patient and the neurosurgeon performing the surgery.

What is a VP shunt and how does it work?

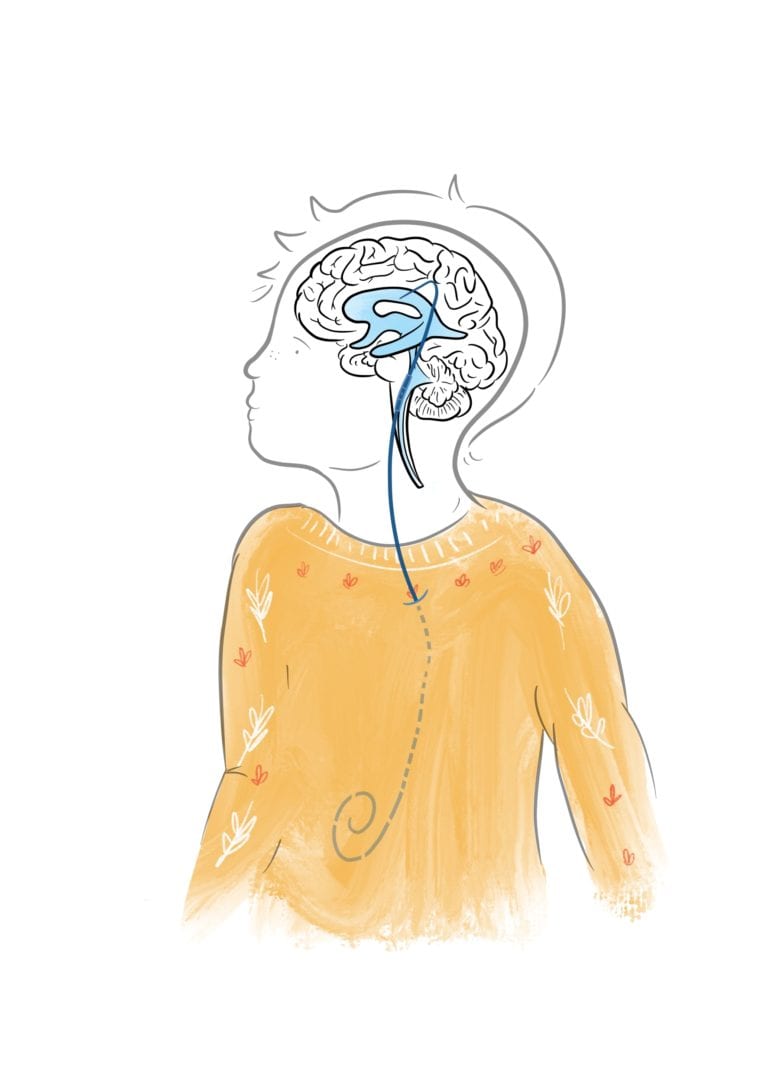

A shunt is a thin tube that is permanently implanted to allow removal of the excess fluid to somewhere else in the body where it can be absorbed. VP shunts are placed into the brain into the ventricle system, and tubing is plumbed down to your abdomen where the excess fluid from your brain will be drained to, and eventually reabsorbed.

A VP shunt is composed of three parts:

1. A one-way valve with a reservoir. This valve only allows movement of fluid in one direction, away from the brain.

2. A short catheter: a thin flexible tube, with a tip placed into the ventricle where the CSF is being produced.

3. A long catheter: a thin flexible tube connecting the short catheter via a valve to the abdomen, where the fluid is drained and reabsorbed back into the body.

The amount of fluid that is drained by your VP shunt depends on settings which are determined by your neurosurgeon.

The complete system is essentially plumbing directly from the patient’s brain down towards the abdominal cavity.

How are they inserted?

In order to correctly and precisely place the shunt, you will need to be under general anaesthetic for about one hour. Once you are asleep, the doctor will shave off small area of your hair, where the incision will be made. There will be two to three small incisions in total: one in your head, one in your neck (possibly) and one in your abdomen. A burr hole is drilled to allow access to the brain, where the short catheter is inserted into the ventricle system. The rest of the long catheter is tunnelled just under the skin down to the abdomen where the fluid will drain. We often use an image-guidance or navigation system to make sure that the tubing placed in the ventricle system is in the perfect position.

Before all of the wounds are closed, the medical team will check that the shunt is working and that the CSF is appropriately being removed from the brain.

If you want to watch real surgical footage of a VP shunt insertion, check out the video below. This is real footage of surgery so is graphic in nature:

Are there any risks involved?

As with any other surgery, placement of VP shunts carries some risks and possible complications. For those reasons, patients undergoing this procedure will be closely monitored on the ward for a few days after their surgery.

The main complications we look out for are bleeding in the brain and infection. These are unavoidable risks, since the tubing passes through the brain in order to correctly place the shunt. Surgeons will choose a point for the tubing to pass through where damage to the brain will have very little effect on how your brain works.

In addition, placement of a foreign object can itself be the cause of an infection. However you shouldn’t worry about this too much, because your surgical team are using highly practiced aseptic techniques that maximally reduces the chances of any infection after surgery. Additionally you will be given antibiotics as a preventative measure, in case an infection were to develop, your body will be ready to fight it off.

Some headache is expected after the surgery, however a long-term headache is not a good sign. Long-term headache could imply that there is over-drainage or under-drainage of CSF from the brain. Under-drainage can be caused by either the displacement or blockage of the shunt. Either situation is not ideal, and we will need to either flush or readjust your shunt, but your surgeons might also need to completely replace it.

When you go home after you’ve been discharged, it is important to know what ‘red flags’ to look out for. If you start experiencing any of the following it is important that you seek urgent medical attention:

- Fever

- Increased seizures

- Severe headache

- Frequent vomiting

- Drowsiness

- Swelling or oozing from the wound site

Common questions after your shunt is in

How long will I have to stay in hospital?

You will be in the hospital for approximately five days, but this varies from patient to patient.

Will the shunt be visible after the operation?

You should not be able to see the shunt itself. However, you might be able to feel the shunt catheter along your neck

Will I be able to feel the shunt?

You shouldn’t be able to feel the shunt in your brain or abdomen, but you might be able to feel it under your skin along your neck.

Does a shunt last forever and will I have to get it changed?

VP shunts are likely to require replacement after several years. Whan implanted in small children and babies, they are likely to need replacement sooner (after two years) then when implanted in older children and adults.

Will it affect me at work/school?

Unless your shunt is malfunctioning it should not affect you at school or work.

Can I drive after having the operation?

If you are a UK citizen it is important that you inform the DVLA if you have had any kind of brain surgery. They will guide you as to how long you should not drive for.

Can I play sports?

You shouldn’t do any heavy lifting, strenuous activities or contact sport for the first 4 to 6 weeks after your surgery. Aerobic exercise, such as walking is good for your body and you should try to walk at least 2 to 3 times a day for 20 to 30 minutes.

There are various other techniques that neurosurgeons can employ, including more long-term solutions. Click on the pictures below to learn more about them.

Credits

Illustrations By

Merlin

Medical Illustrator

Merlin is an award-winning Medical Illustrator, Writer, Educator and Director of ‘Drawn to Medicine’. She strives to visualise information in a way that makes it universally accessible, educational and engaging for both clinicians, patients and the general public.

Follow her on Twitter: @merlin_draws

Website: drawntomedicine.com

Leave a Reply