If left untreated, acute hydrocephalus can be fatal, so emergency treatment is critical.

If you’re unfamiliar with hydrocephalus and what can cause it, this blog post will tell you everything you need to know.

In neurosurgery, we have several ways of diverting this excess fluid with some being temporary and others being more permanent. One temporary technique which is frequently used in the emergency setting is the insertion of an external ventricular drain (EVD).

What is an EVD and how does it work?

This is literally a thin, soft drainage tube that sits outside the patient’s head, with its tip in the ventricular system we mentioned before. The end of the drain is connected to a measurement system and can be used to monitor the pressure inside the brain. It can also be used as a drug delivery system in infections.

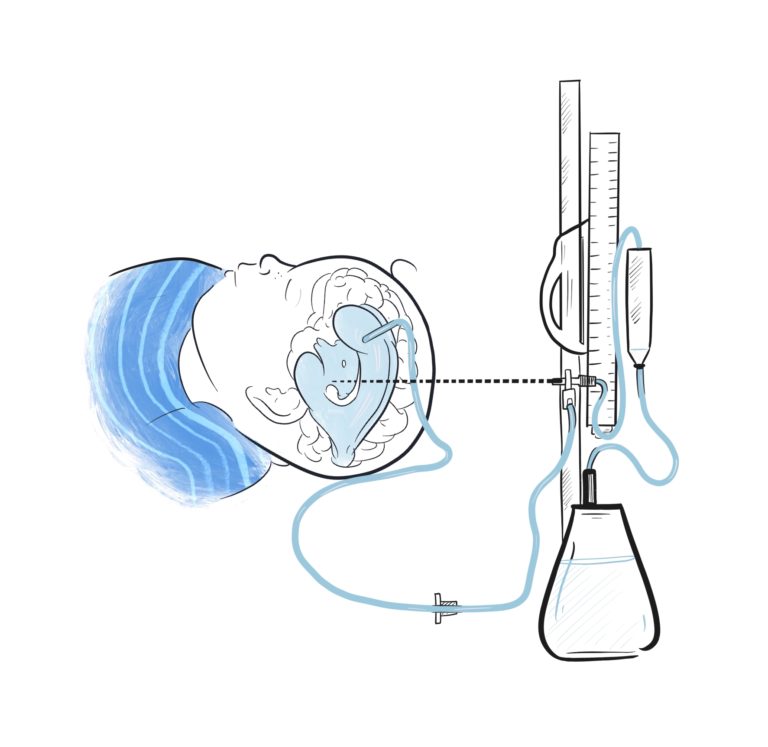

The external drainage system is comprised of a collection chamber which is connected to a drainage bag where the CSF is collected, a pressure scale and a pressure transducer (pic). The pressure transducer is connected to a monitor which allows for the measurement of ICP if needed.

The amount of CSF drainage can be controlled by raising or lowering the external drainage system to different pressures on the pressure scale. CSF will drain whenever the pressure inside the ventricles exceeds that set by the height of the external drainage system. Flow will stop once the pressure in the ventricles and the drainage system is equal. Because of this it’s important to make sure that the height of the drain is set correctly. Any changes in position may mean the drain needs to be repositioned and clamped. The reason for this is that it avoids underdrainage or any over drainage of the CSF from the ventricles.

This is a cartoon of an EVD inserted into the ventricular system of a child. The whole system is “zeroed” to a specific levelso that drainage of fluid is at a constant rate.

How are they inserted?

That’s a really good question. Most commonly, EVD’s are inserted in the operating theatre under sterile conditions. Neurosurgeons have a specific way of locating the optimal point to insert the EVD that avoids critical structures and minimises risk. Watch the video below for a real example of an EVD being inserted. Please be aware that the footage is of real surgery and so is graphic in nature.

Are there any risks involved?

Placement of an EVD is considered an invasive procedure. Just like in all operations, there’s a risk of some complications. One of the main complications we look out for is bleeding. When we insert an EVD we pass through the meninges, which are the layers that cover the brain, and through the brain tissue to the ventricle. Bleeding can therefore occur along this path. As a result, we tend to monitor patients closely on the ward after their EVD placement.

Another risk we look out for is infection. An EVD is a foreign body so it represents a source for bacterial growth. If we do suspect infection, we can take a sample of the CSF from the EVD just like we described above. This helps us know what type of infection is going on and will help guide the treatment.

In some cases, the EVD may not be placed in the correct position or it can sometimes be displaced. If this happens, we can’t accurately measure the ICP and depending on where the drain is, the patient can experience certain symptoms. As a result, the EVD has to be repositioned.

After the procedure, headaches are a common symptom reported in patients. If these headaches are present over a long period of time this can be as a result of over-drainage or under-drainage of CSF. One thing we worry about in under drainage is obstruction of the EVD. This can be quite a serious complication so when this happens, we can either flush or adjust the EVD or we may need to replace it.

How long do they stay in?

This completely depends from situation to situation. No two patients will have the same journey. The risk of infection increases towards the end of a two week-period so at that point three things can happen; it will be taken out, it will be replaced, or a decision will be made to permanently divert CSF. An example of this would be the insertion of a ventriculo-periotoneal shunt. As it happens, we’ve got an article and video all about those here.

There are various other techniques that neurosurgeons can employ, including more long-term solutions. Click on the pictures below to learn more about them.

Credits

Nicola

5th Year Medical Student

Nicola is a 5th year medical student in Aberdeen. Nicola is interested in global neurosurgery and undertook her medical elective in Nepal. Nicola is also passionate about encouraging and inspiring more females into the field of surgery, particularly neurosurgery. Out with Medicine, Nicola enjoys paddle boarding and surfing.

Follow her on Twitter: @newall_nicola

Illustrations

Merlin

Medical Illustrator

Merlin is an award-winning Medical Illustrator, Writer, Educator and Director of ‘Drawn to Medicine’. She strives to visualise information in a way that makes it universally accessible, educational and engaging for both clinicians, patients and the general public.

Follow her on Twitter: @merlin_draws

Leave a Reply