1. What is Cancer Pain?

Pain, as eminent surgeon-writer Atul Gawande puts it, us a symphony. A complex response that includes not just a distinct sensation but also motor activity, a change in emotion, a focusing of attention, a brand-new memory,” [1].

Put more simply, it is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience [2] that can negatively affect patients at different life trajectories.

Cancer Pain is a complex multifactorial phenomenon in patients with malignant disease. It remains an entity that is still not well understood and is one of the most feared symptoms in patients, evolving with disease, treatment, and time.

Globally, the prevalence of cancer is rising and secondary to it is the prevalence rate for cancer pain. Despite a profusion of literature in the past decade, advancing understanding of cancer mechanisms, improved cancer management, and the development of novel approaches, pain prevalence has remained somewhat consistent.

In fact, one third of patients with cancer are actually under-treated for their pain, implicative of a concerning incommensurability between cancer pain and cancer pain management [5].

2. Causes of Cancer Pain

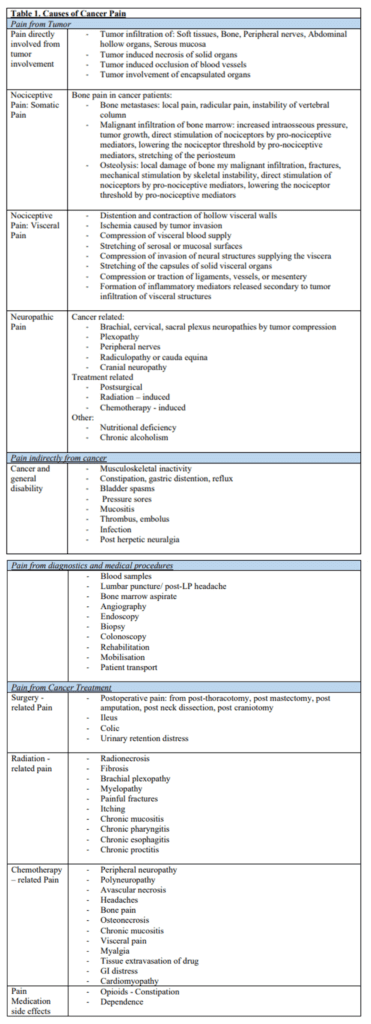

Pain experienced by a oncological patient may not specifically be related to the tumour itself. There are numerous factors causing pain in cancer patients and can be subdivided into [6]:

- Pain from Tumour

- Compression on muscles, bone, nerves, spinal cord, organs

- Pain indirectly related to cancer such as infections

- Infections, metabolic imbalances, myofascial pain

- Pain from Medical Tests

- Biopsy, Spinal Tap, Bone Marrow Tests

- Pain from Treatment

- Surgery -related, Radiotherapy – related, Chemotherapy- related

- Pain completely unrelated to the cancer itself or its treatment

- Arthritis, low back pain, migraines, diabetic neuropathy

- Pain that is present in non-oncological peers can manifest in cancer patients too

*For a more extensive list of causes, please refer to Table 1. in section 8

3. Classification and Assessment of Cancer Pain

The European Pallative Care Research Collaborative [7] undertook a large review of assessment tools for cancer pain and found that there was no single tool that had all of the domains that each other tool had, and concluded that there is no current universally accepted assessment tool for cancer pain that would improve prognosis and direct treatment.

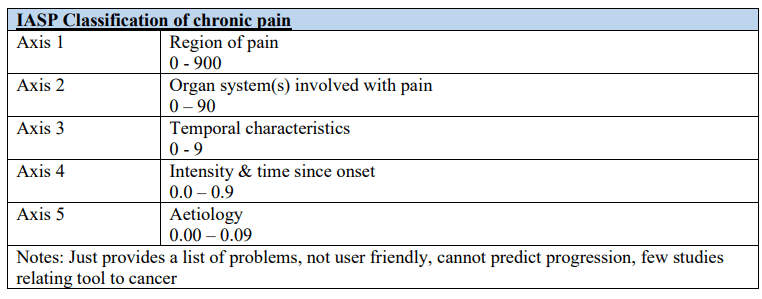

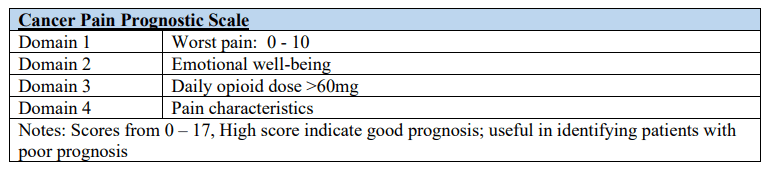

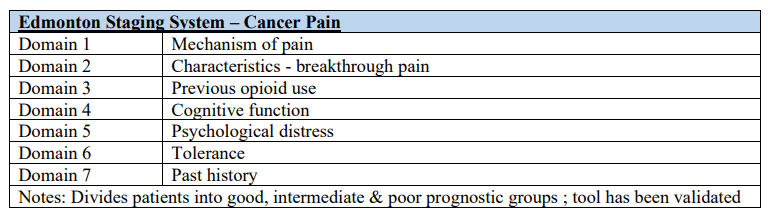

Common tools that have been used to assess cancer pain include IASP Classification of chronic pain, Cancer Pain Prognostic Scale, Edmonton Staging System.

Additionally, pain characteristics communicated through history taking are commonly used in clinical practice to classify or categorize pain in specific domains, and in turn drive pain management[7] :

3.a. Pain intensity

Intensity is regarded as the gold standard for pain assessment and is commonly measured with the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) and Verbal Rating Scale (VRS). In NRS, 0 indicates “no pain” and 10 “the worst pain felt”. NRS divides its severity into : mild (NRS 1-4), moderate ( 5 -6 ) and severe (7-10). Ideally, patients should be asked about “pain at the moment”, “pain at its worst”, “pain on average”, “pain relief” and “pain at its least”. VRS involves patient verbally reporting if pain falls under “mild”, “moderate”, or “severe”. Patients should be educated on how to use these one-dimensional pain scales.

3.b. Pain site

Cancer can affect any body tissue and pain can be experienced in accordance to its anatomic location or “referred”. Especially for pain related to metastatic cancer, there can be more than one site of pain. Pain site is recorded using body maps.

3.c. Pain syndromes

Cancer pain syndromes typically describes a constellation of pain features, physical signs, and results of diagnostic testing. Often the recognition of pain syndromes are dependent on the clinician’s experience and expertise.

3.d. Timing and Temporal Variation

Temporal assessment include information concerning onset type, duration, course and fluctuations. These can be divided into:

- Acute Pain: a quick onset and usually lasts less than 3 – 6 months

- Chronic Pain: persistent pain lasting longer than 3 – 6 months

- Breakthrough Pain:

- Transient exacerbation of moderate to severe pain occurring on a background of chronic pain that is adequately controlled by an analgesic regimen; this flare of pain is typically short lived, severe, episodic and have a sudden onset.

- Usually have a direct relation to cancer, a cancer treatment or a diagnostic test. For example, when dose of the medication wears off – “end dose failure”.

- Refractory Pain: pain unrelieved by therapeutic interventions

4. Types of Pain

On a pathophysiological level, the common pathways and molecular signalling present in tumour development, metastasis and the propagation of cancer pain can inform pain causes, assessment and treatment. To start, understanding the two broad categories of pain is important.

4.a. Nociceptive Pain

The neurons responsible for sensing painful stimuli such as a papercut or a burn from a hot water bottle are sensory neurons called nociceptors, which lay close to the spine and extend into different parts of the body. Nociceptive pain occurs through a neural process of encoding these harmful stimuli from an actual or threatened damage of non-neural tissues [9].

Nociceptive pain can be classified depending on the level of the structures affected, into somatic (superficial structures) and visceral pain (relating to organs within the body’s various cavities). In Cancer Pain, the sensitisation and so increased detection/perception of pain is due to a combination of the presence of tumour-producing cytokines, tumour necrosis factors releasing nociceptive mediators and proteolytic activity from tissue damage.

- Somatic cancer pain refers to malignant invasion of the skin, connective tissue, bone or joints and typically is well localised, defined and described as cramping, aching, throbbing.

- Visceral cancer pain is due to activation of nociceptors of viscera tissue (organs) due to infiltration by metastasis or tumour cells. This pain is diffuse, difficult to locate and may become ‘referred pain,’ where pain is felt in distant superficial structure away from the suffering visceral structure.

4.b. Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic pain results from alterations or dysfunction of the peripheral or central nervous system. Pain descriptors of symptoms include shooting, pins & needles, electric shocks, burning, prickling, tingling. Signs include pain triggered by touching or decreased sensitivity to pricking or light touch [8,10].

4.c. Mixed Pain

Includes both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. This could occur when a nociceptive pain causes secondary lesion over time in the somatosensory nervous system resulting in neuropathic pain.

5. Treatment of Cancer Pain

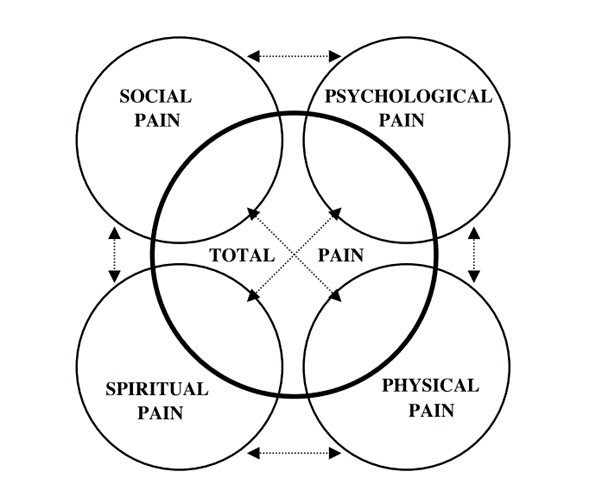

The multidimensional nature of cancer pain includes physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects. All these elements are sources of pain and suffering for patients, and thus needs to be addressed when treating cancer pain.

Figure: Total Pain Components [11]

Thereby the aim of pain management is not only to target one aspect of one’s life but to optimise pain treatment outcomes in all dimensions. Therefore, management is multidisplinary and can be divided into “5As” and these include [12]:

- Analgesia: optimise analgesia (pain relief)

- Activities: optimise psychosocial functioning, allowing maximisation of independence and daily living activities

- Adverse effects: minimise adverse events

- Aberrant drug taking: avoid aberrant drug taking, this includes addiction-related outcomes

- Affect: address mood

5.a. Pharmacological Management

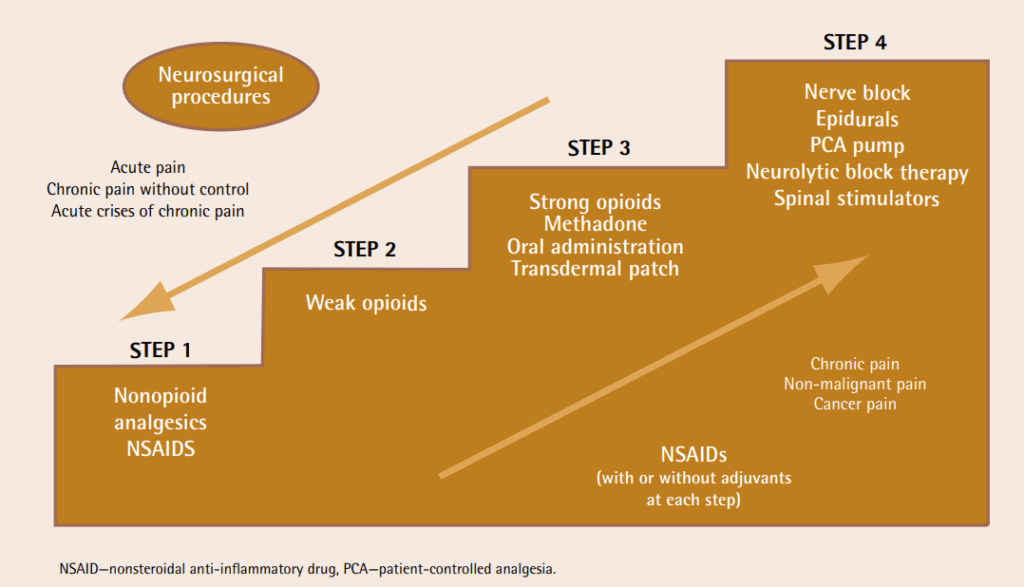

The current era of cancer pain pharmacological treatment began in the mid – 1980s with the World Health Organisation (WHO) 3- step analgesic pain ladder, providing a simple and systemic approach to managing cancer pain. With this ladder approach, it has been reported that 80% of pain are managed. However, for the remaining 20% pain is uncontrolled. Therefore, the WHO ladder have been modified to include a fourth step [13] .

Figure: Modified WHO analgesic ladder [14]

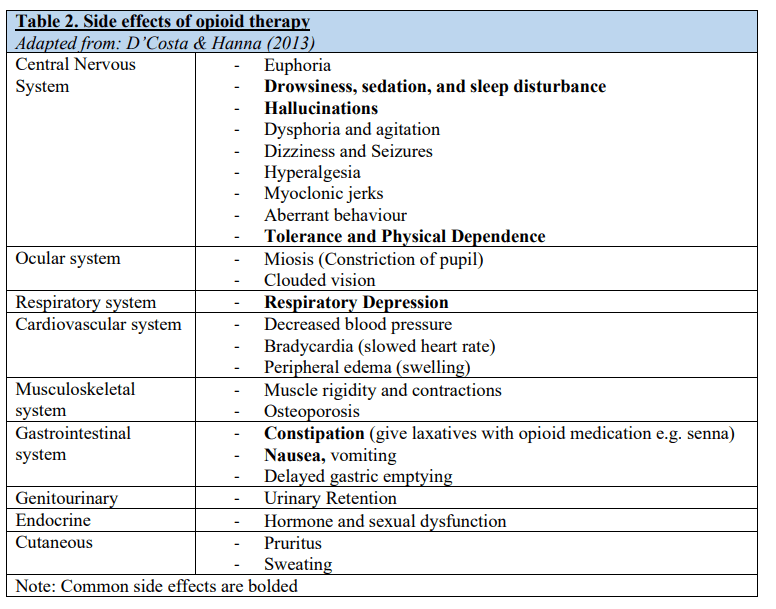

Currently opioids remain the cornerstone of cancer pain treatment but with an increasing understanding of their side effects profile**(Refer to Table 2. in section 8)**, their roles have been changing in clinical settings.

NSAIDs, antiepileptics, antidepressants, NMDA antagonists, sodium channel blockers, topical agents and the neuraxial route of drug administration can all play a part in the treatment of complex cancer pain.

It is important to individualise each management plan and implement measures such as psychological interventions, neuromodulatory therapies, usage of naloxone for high-risk patients, frequent follow-up visits and tapering opioid therapy for example (i.e. steadily reducing said therapy). For each patient, finding the balance between adequate pain control, appropriate analgesia and minimisation of side effects can often complex and challenging.

5.b. Medical management with Non-pharmacological options

Management of pain can include non-pharmacological options such as Acupuncture, hypnosis, placebo analgesia, distraction therapies or physiotherapy/rehabilitation.

The premise for choosing non-pharmacological tools is associating it with the simplest and safest technique. These would, of course, be associated with the highest likelihood of achieving adequate pain relief and increase in one’s quality of life. [15,16]

Interventional therapy

- Neuroablative techniques may be used to interrupt pain transmission by cutting off the relevant nerve supply. These techniques are usually used in refractory cancer pain and include percutaneous cervical cordotomy and celiac and hypogastric neurolytic plexus block [17].

5.c. Addressing Psychological Pain

Physiological distress increases proportionally to the intensity of cancer pain and can markedly affect a patient’s quality of life. Personal beliefs, coping behaviour, social contextual factors, emotional responses are core targets of psychological management in cancer pain [16].

- Coping Skills Training

- Cognitive and behavioural skills for pain management, promoting an active self management approach and reducing stress

- Attention – Diversion Strategies

- Redirect attention to external or internal stimulation, reducing awareness of pain

- Cognitive Coping Strategies

- cognitive rewiring and facilitates more adaptive coping thoughts.

- Pain Management Programmes

- Education and guided practice delivered by a multidisciplinary team

- Usually delivered in a group format, normalising pain experiencing

5.d. Managing Neuropathic pain

Cancer – related neuropathic pain has a good success with a combination of morphine, gabapentin, amitriptyline and steroids however a poor response rate to typical antineuropathic treatment is seen in neuropathic pain secondary to chemotherapy [16].

6. Barriers to adequate pain treatment for cancer patients [18]

6.a. Patient -related barriers

- Reluctance to report pain

- Non-adherence to treatment regimen/recommendations

- Concerns about analgesic use (fear of addiction, tolerance, and side effects)

- Concerns about pain communication (willing to tolerate pain, do not want to let their doctor down, priorities that doctors cure cancer instead of relieving pain)

- Concerns that the pain is an indicator of the cancer worsening

- Self denial, that pain means losing autonomy

- Maladaptive beliefs about possibility to control pain in general and the belief that pain related to cancer is inevitable

- Lack of trust in health care

- Concerns about family reaction to reported pain

- Cultural-social-economical background of patients may acknowledge or see pain differently

6.b. Physician-related barriers

- Reluctance to ask or adequately listen to patient about their pain leading to inadequate pain evaluation

- Lack of assessment or instruments to measure and assess pain.

6.c. Institutional barriers

- Disruption of patient’s continuity of care where patients are seen by different physicians or shift between different health care settings

- Nearly 80% of the world’s population do not have access to opioids. Reasons as stated by WHO are due to bureaucratic regulations restricting opioid supply and prescription, limited education and support of pain services and economic reasons [13].

7. For those fighting cancer pain: Be your greatest advocate

- Keep a Pain diary.

- Effective physician-patient communication is the foundation of successful pain management. It is vital for you to discuss your pain and quality of life with your doctor and healthcare team, and ask for a referral to a pain specialist if you need.

- Adhere to your medication plan.

- You are not alone. It is okay to talk about pain. Your pain can be managed and controlling your pain is part of cancer treatment. Cancer ≠ Suffering

Cancer Pain is difficult to go through, to treat and to frame. It is important to understand that each individual’s narrative of their pain is different and it is the multidisciplinary team’s responsibility to make sure that their goals align with that of the patients.

8. Tables

9. References

- Gawande A. Complications. New York: Metropolitan Books; 2002.

- Higginson IJ, Murtagh FE, Osborne TR. Epidemiology of pain in cancer. InCancer pain 2013 (pp. 5-24). Springer, London.

- Van Den Beuken-Van MH, Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Janssen DJ. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2016 Jun 1;51(6):1070-90.

- Van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, De Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, Van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Annals of oncology. 2007 Sep 1;18(9):1437-49.

- Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, Deandrea S, Bandieri E, Cavuto S, Apolone G. Quality of cancer pain management: an update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Dec 20;32(36):4149-54.

- Fitzgibbon DR, Richard CR. Cancer pain: Assessment and diagnosis. In: Bonica’s Management of Pain. In: Loeser JD, Butler SH, Chapman CR, Turk DC, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 623–58.

- Knudsen AK, Aass N, Fainsinger R, Caraceni A, Klepstad P, Jordhøy M, Hjermstad MJ, Kaasa S. Classification of pain in cancer patients–a systematic literature review. Palliative Medicine. 2009 Jun;23(4):295-308.

- R & Dhingra, L. (2020). Assessment of cancer pain [online] < https://www.uptodate.com/contents/assessment-of-cancer-pain > [Accessed 22/02/2021]

- Caraceni A, Shkodra M. Cancer pain assessment and classification. Cancers. 2019 Apr;11(4):510.

- Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, Hansson P, Hughes R, Nurmikko T, Serra J. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008 Apr 29;70(18):1630-5.

- Mehta A, Chan LS. Understanding of the concept of” total pain”: a prerequisite for pain control. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2008 Jan 1;10(1):26-32.

- Swarm RA, Paice JA, Anghelescu DL, Are M, Bruce JY, Buga S, Chwistek M, Cleeland C, Craig D, Gafford E, Greenlee H. Adult cancer pain, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2019 Aug 1;17(8):977-1007.

- D’Costa RA, Hanna M. Opioids, their receptors, and pharmacology. InCancer Pain 2013 (pp. 109-119). Springer, London.

- Vargas-Schaffer G. Is the WHO analgesic ladder still valid?: Twenty-four years of experience. Canadian Family Physician. 2010 Jun 1;56(6):514-7.

- Lecybyl R. The Non-Pharmacological and Local Pharmacological Methods of Pain Control. InCancer Pain 2013 (pp. 143-151). Springer, London.

- Raphael J, Ahmedzai S, Hester J, Urch C, Barrie J, Williams J, Farquhar-Smith P, Fallon M, Hoskin P, Robb K, Bennett MI. Cancer pain: part 1: Pathophysiology; oncological, pharmacological, and psychological treatments: a perspective from the British Pain Society endorsed by the UK Association of Palliative Medicine and the Royal College of General Practitioners. Pain medicine. 2010 May 1;11(5):742-64.

- Schweiger V, Polati E, Paladini A, Varrassi G. Interventional Techniques in Cancer Pain: Critical Appraisal. InCancer Pain 2013 (pp. 231-247). Springer, London.

- Jacobsen, R., Liubarskienë, Z., Møldrup, C., Christrup, L., Sjøgren, P., & Samsanavičienë, J. (2009). Barriers to cancer pain management: a review of empirical research. Medicina, 45(6), 427.

- https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2013/10/d05-p-c.pdf

- https://thejns.org/pediatrics/view/journals/j-neurosurg-pediatr/14/4/article-p418.xml

Credits

Vanessa Chow

Brainbook Editorial Officer

At the time of writing, Vanessa is a final-year medical student at St George’s University of London.

Great post! Cancer pain management requires a comprehensive and compassionate approach, considering both the physical and emotional aspects of pain. Collaborating with a healthcare team experienced in cancer care and pain management is crucial to provide the best possible relief for individuals living with cancer.